The Flowers Blooming in the Dark

from New York Review of BooksIt’s possible to identify another period that might surpass the 1980s as China’s most open: a 10-year stretch beginning around the turn of this century, when a rich debate erupted over what lay ahead. As in the past, many of those speaking out...

The U.S.-Made Chinese Future That Wasn’t

Soon, such a scene would become unthinkable. It was a cold morning in early March 1946, a rocky airstrip laid along a broad, barren valley in China’s northwest, lined by mountains of tawny dust blown from the Gobi Desert. Six months earlier, one...

How the Cultural Revolution Changed China Forever

Frank Dikotter, author of The Cultural Revolution: A People's History, discusses the turning point in modern Chinese history.

The Bloodthirsty Deng We Didn’t Know

from New York Review of Books“Deng was…a bloody dictator who, along with Mao, was responsible for the deaths of millions of innocent people, thanks to the terrible social reforms and unprecedented famine of 1958–1962.” This is the conclusion of Alexander...

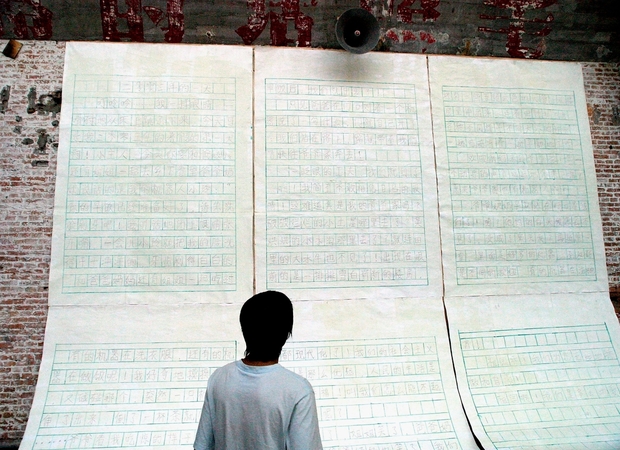

Mao’s China: The Language Game

from New York Review of BooksIt can be embarrassing for a China scholar like me to read Eileen Chang’s pellucid prose, written more than sixty years ago, on the early years of the People’s Republic of China. How many cudgels to the head did I need before arriving at...

Muslim, Trader, Nomad, Spy

In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled Lhasa, leaving the People's Republic of China with a crisis on its Tibetan frontier. Sulmaan Wasif Khan tells the story of the PRC's response to that crisis and, in doing so, brings to life an extraordinary cast of characters: Chinese diplomats appalled by sky burials, Guomindang spies working with Tibetans in Nepal, traders carrying salt across the Himalayas, and Tibetan Muslims rioting in Lhasa.

China’s Brave Underground Journal—II

from New York Review of BooksIn downtown Beijing, just a little over a mile west of the Forbidden City, is one of China’s most illustrious high schools. Its graduates regularly attend the country’s best universities or go abroad to study, while foreign leaders and CEOs make...

China’s Brave Underground Journal

from New York Review of BooksOn the last stretch of flatlands north of Beijing, just before the Mongolian foothills, lies the satellite city of Tiantongyuan. Built during the euphoric run-up to the 2008 Olympics, it was designed as a modern, Hong Kong–style housing district...

China: Reeducation Through Horror

from New York Review of BooksHere are two snippets from a Chinese Communist journal called People’s China, published in August 1956:

In 1956, despite the worst natural calamities in scores of years, China’s peasants, newly organized in co-

...

The Tragedy of Liberation

“The Chinese Communist party refers to its victory in 1949 as a ‘liberation.’ In China the story of liberation and the revolution that followed is not one of peace, liberty, and justice. It is first and foremost a story of calculated terror and systematic violence.” So begins Frank Dikötter’s stunning and revelatory chronicle of Mao Zedong’s ascension and campaign to transform the Chinese into what the party called New People.

Anyuan

How do we explain the surprising trajectory of the Chinese Communist revolution? Why has it taken such a different route from its Russian prototype? An answer, Elizabeth Perry suggests, lies in the Chinese Communists’ creative development and deployment of cultural resources – during their revolutionary rise to power and afterwards.

China’s Risky Path, from Revolution to War

The scenario of abrupt bottom-up revolution occurring in China has recently generated much debate.

China: The Shame of the Villages

from New York Review of Books1.

Published fifteen years ago, Chinese Village, Socialist State, as I wrote at the time, not only contained a more telling account of Chinese rural life than any other I had read; it also produced a new understanding “of the...

China: The Uses of Fear

from New York Review of BooksInstilling deadly fear throughout the population was one of Mao Zedong’s lasting contributions to China since the late Twenties. In the case of Dai Qing, one of China’s sharpest critics before 1989, fear seems to explain the sad transformation in...

The Party’s Secrets

from New York Review of BooksNot long after Mao Zedong died in 1976, one of the editors of the Party’s People’s Daily said. “Lies in newspapers are like rat droppings in clear soup: disgusting and obvious.” That may have been true of the Party’s newspapers, which...

Mao and Snow

from New York Review of BooksNorth Vietnam and China: Reflections on a Visit

Early this year I went to Hanoi by way of China. After spending a week in Peking I went to North Vietnam for just over a month and then returned to China, where I stayed in Changsha and Canton for two weeks. Later I spent three and a half weeks...

Contradictions

from New York Review of BooksProfessor Schurmann is not modest. Near the beginning of his book he writes: “translations from Chinese, Russian and Japanese are my own, and hundreds of articles had to be read in the original Chinese with precision and at the same time...

How to Deal with the Chinese Revolution

from New York Review of BooksThe Vietnam debate reflects our intellectual unpreparedness. Crisis has arisen on the farthest frontier of public knowledge, and viewpoints diverge widely because we all lack background information. “Vietnam” was not even a label on our horizon...

Mao’s China

from New York Review of BooksTo most Westerners China is not a part of the known world and Mao is not a figure of our time. The ignorant believe he is the leader of a host of martians whose sole occupation is plotting the destruction of civilization and the enslavement of...

The Popularity of Chinese Patriotism

from New York Review of BooksFundamentally China is a sellers’ market. The first half of this century, when there was a glut of books, seems to have been the exception. Since 1949 a veil has once more been drawn over the center of the mysterious east, and the situation has...