This project on Hong Kong began in Paterson, New Jersey. In 2016-2017, I was studying at the International Center for Photography and photographing the place I grew up. I wanted to find a way to connect with local gangs.

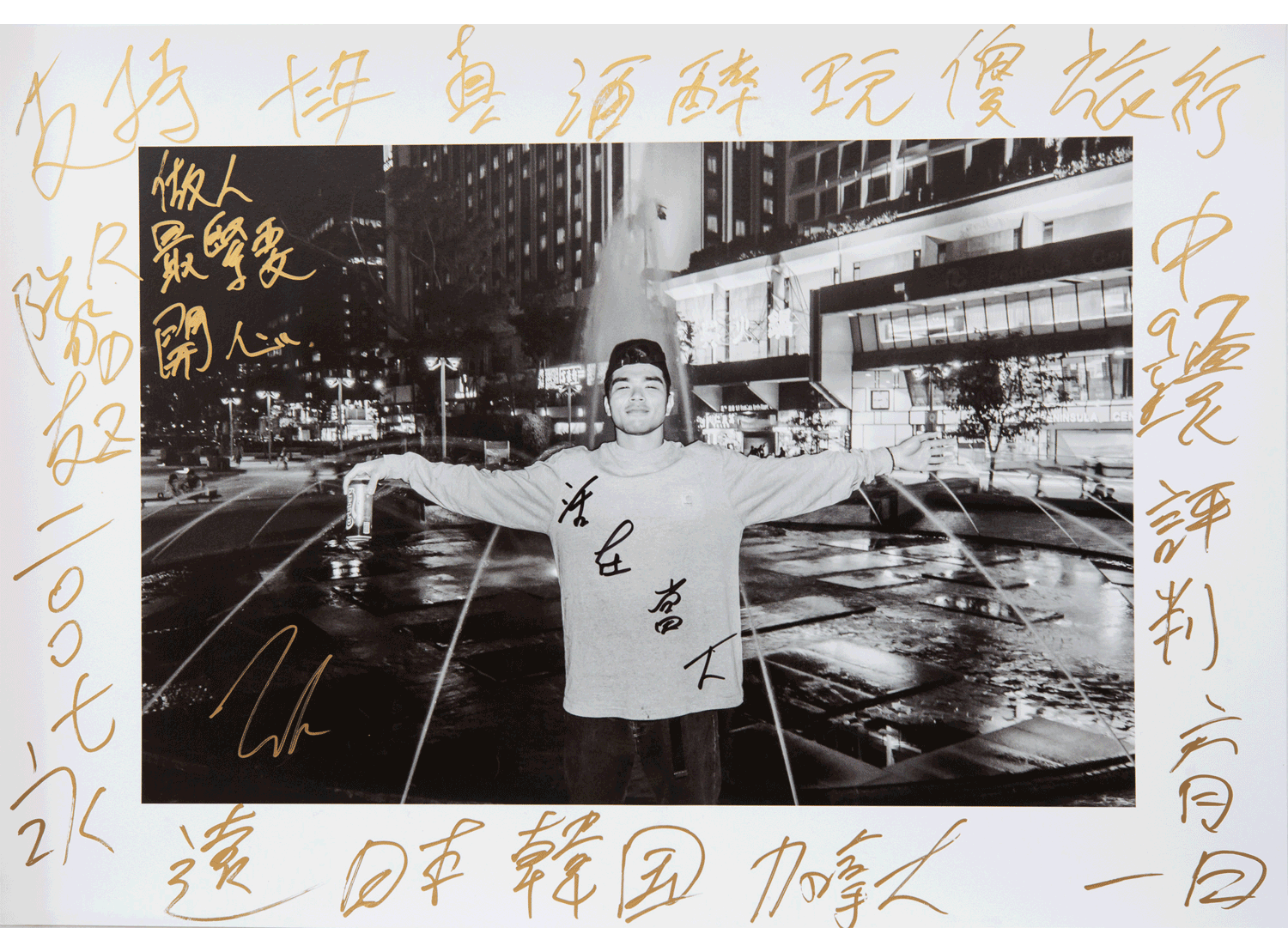

I began making portraits of people in Paterson and having the subjects write on the photos in order to tell more expressive stories about themselves and their community. Some of my portrait subjects are aspiring rappers, many others are not, and they all face adversity through various forms of oppression. In Paterson, oppression comes in the form of racism, violence, poverty, corruption, and addiction.

After graduating in 2017, I returned to Hong Kong, where I have now been living for around 13 years, and I continued the project here. Individually, the portraits and text may tell a simple story about daily life or address larger issues such as universal suffrage or inequality, but as a whole I hope they tell a nuanced story about Hong Kong and its people. The current political situation in Hong Kong has affected the direction of the project, pushing it to include how Hong Kong people feel about the receding of freedoms that in the past felt secure: freedom of the press and expression, the right to assembly and to participation in political affairs, and an independent judiciary.

Thus far, I have focused primarily on musicians, particularly members of the rap groups LMF and 24Herbs, and b-boys (breakdancers). But recently I added Josie Ho, a rock and punk singer and actress, and began including activists like Joshua Wong and Yau Wai-ching, who was expelled from Hong Kong’s Legislative Council because of the way she said the word “China” when taking her oath of office. As the project continues, I plan to include more young people who have been participants in recent demonstrations, and then broaden my focus to include other parts of Hong Kong society.

The process for making the photos is a collaboration. I suggest that people consider what they want to say about their lives and select a place significant to them as the setting for the portrait. I scout the location and attempt to create an image there that reflects the character of the person and the idea they want to communicate so that the text and the photograph work off of each other to enhance the final piece. The final step includes making the print in my studio and meeting with the participants so they can add their text to the print.

A central issue many of the Hong Kong people in my portraits are wrestling with is how to define an identity and being challenged in that pursuit by cultural, social, or political pressures. There is a lot of frustration and anger over the recent attempted implementation of an extradition law allowing people in Hong Kong to be tried in mainland China, and over alleged police brutality during subsequent protests. This is apparent in one particular portrait where a subject posed with a gun to their head.

Some artist-participants express frustration over familial pressure to conform to parental expectations in their professional lives. Some worry Hong Kong’s aesthetic is changing and housing is unaffordable. Others say they are troubled by Hong Kong’s materialism. What’s not expressed in the portraits but important to mention is that self-censorship is already affecting some artists I’ve met whose livelihoods rely on mainland China.

In a way, everyone is asking some version of the question of what it means to be from Hong Kong and what it will mean in the future.

{photo, 50991}

{photo, 50976}

{photo, 50981}

{photo, 50996}

{photo, 50971}

{photo, 51001}

{photo, 51006}

{photo, 51011}

{photo, 51016}

{photo, 51021}

{photo, 51026}

{photo, 51031}

{photo, 51036}

{photo, 51041}

{photo, 51046}

{photo, 51051}

{photo, 51056}

Zhaoyin Feng assisted with transcription and translation.